by Lauren DeLorenzo, Journalist, Energy magazine

Melbourne’s iconic CBD bathed in sunlight is quite a spectacular view — but now the city’s sun-soaked skyline can offer more than just a killer Instagram photo. New research from Monash University has unveiled the massive potential of solar photovoltaics (PV) integration in transforming Melbourne into a near-self-sustaining city.

Cities suck up huge amounts of energy, but produce very little themselves. New research from Monash University has revealed a massive opportunity for Melbourne, and cities like it, to shift this balance.

The study, first published in the journal Solar Energy, found that integrating solar technology in roofs, walls, and windows could account for up to 74 per cent of Melbourne’s electricity supply. The bulk of that solar energy supply (88 per cent) could be produced through rooftop solar alone.

Wall-integrated and window-integrated solar technologies, which could be used to capture solar radiation bouncing off of city skyscrapers, could produce 8 per cent and 4 per cent of that supply, respectively.

Researchers from the ARC Centre of Excellence in Exciton Science based at Monash University worked with collaborators at the University of Lisbon to chart the amount of sunlight that reaches the city annually, taking into account shadows from taller buildings.

By mapping the solar radiation, researchers were able to create an adaptable model which can estimate the maximum solar power generation potential of Melbourne. Co-author and Lecturer for Environmental and Civil Engineering at Monash University, Dr Jenny Zhou, said the workflow of the study was made deliberately transparent to encourage more types of this research in other cities.

“The simulation models we used in our study are open source tools with little or no cost,” Dr Zhou said. “So any other cities can borrow the model from our study and produce their own estimates.”

The research focused on the 37.4km section of central Melbourne – an area that consumes around 7.5 per cent of the state’s entire energy supply.

First author of the study and private sustainability expert, Dr Maria Panagiotidou, said there are clear benefits to implementing solar PV.

“Solar is widely available and technology has made incredible steps in the last 20 years,” Dr Panagiotidou said. “So it’s quite important to be able to capture this energy, which is an opportunity that would otherwise be wasted. We wanted to, through this research, demonstrate the absolute maximum potential of this.”

Unlocking Melbourne’s solar potential

Melbourne’s energy demand is highest during the day, when people are using energy inside city buildings — during the times when solar is most able to provide additional supply.

Localised energy production during these hours of sunlight could have significant cost and resource-saving implications for Melbourne. With electricity generation typically sourced from the LaTrobe Valley, electricity losses can occur during transmission to the city.

Corresponding author and Professor of Engineering at Monash University, Jacek Jasieniak, said that local energy production avoids “quite sizeable” losses of electricity. Electricity transmission from LaTrobe Valley to Melbourne began in the 1920s; before that, Melbourne ran on local generators.

Now, localised energy production in Melbourne could be a key energy solution. “It almost seems like there’s an opportunity to go back a hundred years, but actually reinvent and rethink the sustainability and the cost benefits of doing that,” Professor Jasieniak said.

Rethinking buildings for solar integration

So what steps are needed to make the most of solar PV in Melbourne? Dr Zhou explained that although rooftop solar has proven to be the most viable solar technology for broad energy production, the challenge is incentivising its implementation in existing sites.

“Our study implies a policy gap in building refurbishment, because transforming the city services to solar energy collectors requires retrofit of the existing building,” Dr Zhou said. “But the relevant policies that support this kind of change aren’t there.”

For new sites, the planning process needs to consider the viability of solar PV within the building’s urban environment, and how that might change in the future. “It goes beyond a building to a more systemic approach in how we view energy at a collective scale,” Professor Jasieniak said.

Another complication comes from competing interests in building development. Building developers and renewable energy experts must find a solution which maximises solar surfaces while optimising building space.

“There’s no reason why Melbourne, if it was properly developed as a CBD, couldn’t be a renewable energy zone, right?” Professor Jasieniak said. “It can produce so much renewable energy. But for that to happen, you need to bring the right people together in a collaborative way. And I suspect at this stage, that piece hasn’t really come through because of competing priorities.”

When it comes to window and wall solar installations, the process is even more logistically challenging. “In those instances, at least for windows, you’d have to physically replace all the window structures, and then you’d need to connect the electrical connections from the windows into the main electrical connection of the building.

Now that is not as straightforward as rooftop,” Professor Jasieniak said. Another challenge to solar integration lies in managing the utility side — how would Melbourne’s solar upgrade engage with the existing energy grid?

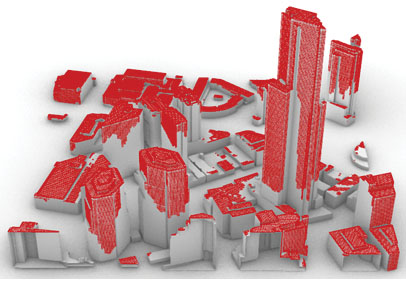

A 3D view of the modelled area shows suitable roof (solar radiation ≥ 1,000 kWh m-2 a-1) and facade areas (solar radiation ≥ 800 kWh m-2 a-1) for the installation of PV modules (red areas).

“The only way to really maximise the utility of those types of installations is by coupling to the actual electrical networks and really understanding, how does a building individually, and as a collection of buildings in a region like the CBD, participate in a market?” Professor

Jasieniak said.

“And what role does energy storage have in actually shifting the electricity? “We should be co-developing what that future would look like with distribution companies, with our wholesale market operator and with other parts of the energy system to understand how to best evolve.”

Dr Zhou said that the challenge of addressing these issues is establishing a common vision for how Melbourne could become an energy generator.

“When we are talking about how we implement PV technologies, there are so many decision-makers in this process, and they are usually separated,” Dr Zhou said. “So I think it’s important to establish a common vision.”

How far can new solar tech take us?

With new technological developments, solar PV is becoming increasingly efficient. Upcoming solar technologies have projected efficiencies that are 20 per cent higher than current devices, allowing for greater solar power generation capacity.

Window and wall solar technologies are still developing, with the next generation of materials evolving to deliver much higher efficiencies. “There’s a lot of materials development, and solar cell device engineering needed to actually develop stable, nontoxic solar window technologies, that can be integrated into buildings at the scale that we need them to be integrated,” Professor Jasieniak said.

Dr Zhou said, “There’s always a trade-off for solar window technologies… how can we increase the generation efficiency and then at the same time satisfy occupants’ need for natural light?”

Challenging the way we see energy infrastructure

While developments in solar technologies can unlock new emissions-reduction opportunities, Dr Panagiatidou said that even wide-scale adoption of solar PV might not be enough with current solar efficiencies.

“Even if we do cover whole cities with solar PV… we still cannot reach net zero,” Dr Panagiatidou said. “We still cannot cover the energy consumption of the present, let alone of the future. So in my mind, this highlights the need to actually reduce our energy consumption.

“If we consider current consumption and production, I still believe that there is a big gap. If we say that solar can solve all of our problems, I think we are, at the moment, not right.”

Promising solar PV technologies have the potential to bring Melbourne, and other cities like it, to a position of being almost fully self-sustaining.

Though a completely self-sustaining city might be beyond reach, developing solar technologies could bring Melbourne closer to this goal. The Australian Renewable Energy Agency (ARENA) is investing in ultra low cost solar, which supports PV with 30 per cent module efficiency, bringing Melbourne’s net zero goal in sight.

But technology is just one piece of the puzzle. In order to take full advantage of Melbourne’s solar capabilities, collaboration must be the driving force behind the city’s energy transformation. “From a research point of view, we are striving to develop new kinds of technology,” Dr Zhou said.

“And from the policy point of view, there are some efforts trying to promote the use of renewable energies. “And from the general public point of view, they have an interest in this, but they don’t know how to effectively use it. So we need something to bring everything together.”